A friend of mine recently wrote an excellent post on tattoos, bodily autonomy and parental control, in response to an article on the Guardian which was full of overblown hysterics regarding one mother's reactions to her son's tattoo. I'm crossposting it here, because it's such a good, considered, well thought out response.

-----------------------

As I am in my mid-twenties, and find myself part of a very similar situation, I wanted to respond directly to Tess Morgan’s recent article in the Guardian. And just as I know her hysterical reaction is not indicative of all mothers, I do not assume to speak for anyone other than myself. I also hesitate to make this too-specifically about my own situation as, unlike Tess - only crudely hidden with a pseudonym, I don’t want to step on the toes of anyone else’s privacy. I hope I can paint reactions with broad enough brushstrokes.

Tess’ article reads like a (somewhat overblown) itinerary of my own parents’ reactions to my two tattoos. And although I was reasonably unaware of how revulsed they were by the idea of tattoos before getting inked, it sounds like her son and I had similar experiences.

One key difference is that I am female - usually I would make no issue of this, but Tess explains why her associations of men with tattoos are so strong, and so abhorrent. And this is something that fascinates me. This level of prejudice, from someone claiming to be liberal, is typical of the Guardian reading hypocrisy. It seems her deepest fear is that her son will instantly become (or at least be seen as) a thug with a dog on a chain. This boy is clearly more intelligent and open-minded than his mother. What a terrible advert for middle-class sneering. ‘On a chain!!’

In my case, I am a woman. Largely speaking we are a society absent of older women with tattoos. If they have them, we do not see them. There are likely to be few women currently in their seventies with tattoos. I want to see these taboos broken. I want to be part of changing what women are allowed to explore and expose. Tess realises her reaction may just be what older women feel. I want these prudish expectations of women to evaporate. I no more want to be objectified by a middle-aged woman than I do by any man. The only thing I can do is fight by refusing to cover, for others, the markings I have chosen.

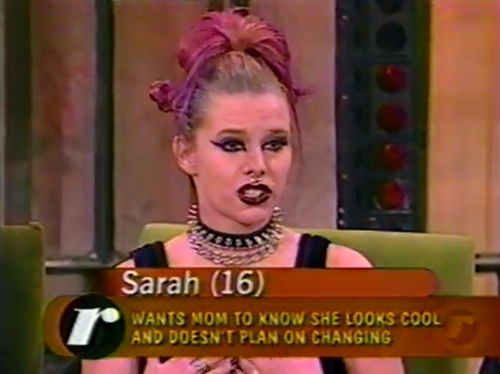

image taken by Tom Cops

When imagining my body at seventy, my parents think I will regret my (carefully considered) choices. But there is something beautiful and freeing in trusting yourself, trusting that, whether or not fashions change and you no longer like the aesthetic you chose, that picture is now a part of your fabric. It has become as familiar and pleasing as any part of your body. You have lived with it for nearly as long. My tattoos were developed with people I love, during some of the best experiences of my life, and even if my relationship to those people were to change, what better reminder of the possibilities of human interaction?

Tess assumes tattoos are fashionable, but that is not right, they are a culture in themselves. And whereas they historically told the world ‘I am part of this specific thing’, with symbols to delineate denominations, they now say whatever an individual chooses.

Tess’ images of death and repeated reference to the fact her son ‘couldn’t have done anything to hurt me more’ are utterly ridiculous and I’m sure only push her level-headed sounding son further away. He has done nothing to her. When he makes any other decision I’m sure he doesn’t have to consider his parents’ judgement, because until that point he has obviously received excesses of unconditional love, reinforcing his every thought.

It seems prejudice is nearly all of what this reaction comes down to. But if a tattoo is going to change how someone thinks of me, well then it is a good way of filtering out the idiots before I get emotionally involved with them. If someone had a problem with what I chose to wear, I would not change for them, as it is a big part of who I am. My parents would not want me to. I had hoped they would see this in that light.

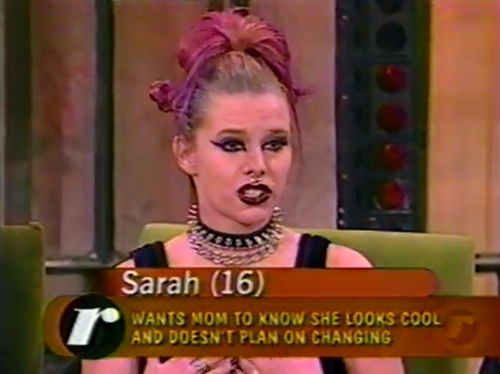

image via

As in the case of Tess’ son, my tattoos are easily covered for working situations, so they will never stop me from achieving the high-powered jobs parents think their children want. And surely a tattoo is an indication of the self-belief and arrogance you need to reach the top of any career chain.

My parents always want me to feel sure of myself, comfortable in my own skin. And despite their limitless faith in me and praise, I am as full of doubt and self-deprecation as everyone else. Getting my two tattoos signalled the first time I had felt certain of anything, the first time I confidently made a decision that benefited and affected only me. I naturally satellite my movements around others, my views are occasionally malleable and open to debate. I spend a lot of time agonising over this. It’s something I’m intensely aware of and something I want to change. I felt immensely happy when, contrary to this trait, I evolved the certainty to add something to myself. Something I would glimpse in the mirror, something for and about myself, and the few people involved in their conception.

It soon transpired the tattoos were not only affecting me, they were affecting my parents even more. The idea that a parent has the kind of connection Tess describes to the body of their child is disturbing. It makes me never want to have children. To assume any kind of authority over someone else’s body, whether or not they started life in your womb or testicles, is not right. Even if that authority originates in love and devotion.

It is my body. It is my body. And just in case it hasn’t sunk in, it is my body. Will and Jada Pinkett Smith said a brilliant thing about their daughter Willow:

“We let Willow cut her hair. When you have a little girl, it’s like how can you teach her that you’re in control of her body? If I teach her that I’m in charge of whether or not she can touch her hair, she’s going to replace me with some other man when she goes out in the world. She can’t cut my hair but that’s her hair. She has got to have command of her body. So when she goes out into the world, she’s going out with a command that it is hers.”

(This should be a picture of Willow Pinkett Smith but the image won't copy over. Please go to Grace's original post to view it)

image via

When Tess hazards that her son gave her no thought when getting the tattoo, she is right. She says he ‘took a meat cleaver to my apron strings’, but what would be a better sign of a loving, empathetic, motherly connection than to accept her son for whatever decisions he makes, whatever he chooses to wear, be or paint himself with? Even if this turns out to be a mistake, for god’s sake support him in that too. You clearly want to be involved.

If anything, Tess has untied the strings with her own hyperbolic rage and petty childish response to snobbish prejudice.

I have still never regretted my tattoos for a single second. But the only thing that has made me feel any unease has been my parents. I am hoping that Tess will do as her son says, re-examine her prejudices and, to put it bluntly, chill the fuck out. My parents have.

--------------------

Wonderfully put Grace. Questions about parent/child bodily autonomy have been at the forefront of my mind recently, as my sister had her first child 5 months ago. My mother has got very protective and controlling about myself, my sister and her new granddaughter since then, and I think it's all tied up with feelings of ownership that she's got over us. Obviously, this makes me very uncomfortable. So, this post is very timely for me.

I do not have any tattoos, but I do have piercings, I've written about them here.

-----------------------

As I am in my mid-twenties, and find myself part of a very similar situation, I wanted to respond directly to Tess Morgan’s recent article in the Guardian. And just as I know her hysterical reaction is not indicative of all mothers, I do not assume to speak for anyone other than myself. I also hesitate to make this too-specifically about my own situation as, unlike Tess - only crudely hidden with a pseudonym, I don’t want to step on the toes of anyone else’s privacy. I hope I can paint reactions with broad enough brushstrokes.

Tess’ article reads like a (somewhat overblown) itinerary of my own parents’ reactions to my two tattoos. And although I was reasonably unaware of how revulsed they were by the idea of tattoos before getting inked, it sounds like her son and I had similar experiences.

One key difference is that I am female - usually I would make no issue of this, but Tess explains why her associations of men with tattoos are so strong, and so abhorrent. And this is something that fascinates me. This level of prejudice, from someone claiming to be liberal, is typical of the Guardian reading hypocrisy. It seems her deepest fear is that her son will instantly become (or at least be seen as) a thug with a dog on a chain. This boy is clearly more intelligent and open-minded than his mother. What a terrible advert for middle-class sneering. ‘On a chain!!’

In my case, I am a woman. Largely speaking we are a society absent of older women with tattoos. If they have them, we do not see them. There are likely to be few women currently in their seventies with tattoos. I want to see these taboos broken. I want to be part of changing what women are allowed to explore and expose. Tess realises her reaction may just be what older women feel. I want these prudish expectations of women to evaporate. I no more want to be objectified by a middle-aged woman than I do by any man. The only thing I can do is fight by refusing to cover, for others, the markings I have chosen.

image taken by Tom Cops

When imagining my body at seventy, my parents think I will regret my (carefully considered) choices. But there is something beautiful and freeing in trusting yourself, trusting that, whether or not fashions change and you no longer like the aesthetic you chose, that picture is now a part of your fabric. It has become as familiar and pleasing as any part of your body. You have lived with it for nearly as long. My tattoos were developed with people I love, during some of the best experiences of my life, and even if my relationship to those people were to change, what better reminder of the possibilities of human interaction?

Tess assumes tattoos are fashionable, but that is not right, they are a culture in themselves. And whereas they historically told the world ‘I am part of this specific thing’, with symbols to delineate denominations, they now say whatever an individual chooses.

Tess’ images of death and repeated reference to the fact her son ‘couldn’t have done anything to hurt me more’ are utterly ridiculous and I’m sure only push her level-headed sounding son further away. He has done nothing to her. When he makes any other decision I’m sure he doesn’t have to consider his parents’ judgement, because until that point he has obviously received excesses of unconditional love, reinforcing his every thought.

It seems prejudice is nearly all of what this reaction comes down to. But if a tattoo is going to change how someone thinks of me, well then it is a good way of filtering out the idiots before I get emotionally involved with them. If someone had a problem with what I chose to wear, I would not change for them, as it is a big part of who I am. My parents would not want me to. I had hoped they would see this in that light.

image via

As in the case of Tess’ son, my tattoos are easily covered for working situations, so they will never stop me from achieving the high-powered jobs parents think their children want. And surely a tattoo is an indication of the self-belief and arrogance you need to reach the top of any career chain.

My parents always want me to feel sure of myself, comfortable in my own skin. And despite their limitless faith in me and praise, I am as full of doubt and self-deprecation as everyone else. Getting my two tattoos signalled the first time I had felt certain of anything, the first time I confidently made a decision that benefited and affected only me. I naturally satellite my movements around others, my views are occasionally malleable and open to debate. I spend a lot of time agonising over this. It’s something I’m intensely aware of and something I want to change. I felt immensely happy when, contrary to this trait, I evolved the certainty to add something to myself. Something I would glimpse in the mirror, something for and about myself, and the few people involved in their conception.

It soon transpired the tattoos were not only affecting me, they were affecting my parents even more. The idea that a parent has the kind of connection Tess describes to the body of their child is disturbing. It makes me never want to have children. To assume any kind of authority over someone else’s body, whether or not they started life in your womb or testicles, is not right. Even if that authority originates in love and devotion.

It is my body. It is my body. And just in case it hasn’t sunk in, it is my body. Will and Jada Pinkett Smith said a brilliant thing about their daughter Willow:

“We let Willow cut her hair. When you have a little girl, it’s like how can you teach her that you’re in control of her body? If I teach her that I’m in charge of whether or not she can touch her hair, she’s going to replace me with some other man when she goes out in the world. She can’t cut my hair but that’s her hair. She has got to have command of her body. So when she goes out into the world, she’s going out with a command that it is hers.”

(This should be a picture of Willow Pinkett Smith but the image won't copy over. Please go to Grace's original post to view it)

image via

When Tess hazards that her son gave her no thought when getting the tattoo, she is right. She says he ‘took a meat cleaver to my apron strings’, but what would be a better sign of a loving, empathetic, motherly connection than to accept her son for whatever decisions he makes, whatever he chooses to wear, be or paint himself with? Even if this turns out to be a mistake, for god’s sake support him in that too. You clearly want to be involved.

If anything, Tess has untied the strings with her own hyperbolic rage and petty childish response to snobbish prejudice.

I have still never regretted my tattoos for a single second. But the only thing that has made me feel any unease has been my parents. I am hoping that Tess will do as her son says, re-examine her prejudices and, to put it bluntly, chill the fuck out. My parents have.

--------------------

Wonderfully put Grace. Questions about parent/child bodily autonomy have been at the forefront of my mind recently, as my sister had her first child 5 months ago. My mother has got very protective and controlling about myself, my sister and her new granddaughter since then, and I think it's all tied up with feelings of ownership that she's got over us. Obviously, this makes me very uncomfortable. So, this post is very timely for me.

I do not have any tattoos, but I do have piercings, I've written about them here.

No comments:

Post a Comment